Building an MVC-Structured Blog Post Web API with Go × Gin: From Basics to Scalable Design

This post is also available in .

Introduction

When building a Web API in Go, Gin is one of the most popular lightweight frameworks. It offers simple syntax and high performance, while also providing flexible routing and middleware mechanisms, making it suitable for everything from small prototypes to medium- and large-scale services.

However, as your codebase grows, it can become unclear “where to put what,” and the impact of changes can become larger.

In this article, we will proceed with the following in mind:

- Clean code design using an MVC (Model, View, Controller) structure

- Directory design that starts small and can scale

- A strategy for evolving into a production-ready structure while leveraging Gin’s basic features

What you will be able to do after reading

- Start up a minimal API server using Gin

- Understand the basics of the MVC structure and the responsibilities of each layer

- Design and build a structure with scalability in mind on your own

This series consists of three parts. From the next article onward, we will dive into practical know-how for production operations, such as tests and CI integration.

First, let’s solidify the foundation by building the API server from the ground up.

The code created in this article is available in the following repository:

Directory structure and file layout

In this article, we will use a Web API for “creating and retrieving blog posts” as our example, and build it based on an MVC (Model-View-Controller) structure that is easy to apply in real-world projects.

go-gin-blog-api/

├── main.go // Application entry point

├── handler/ // HTTP handlers (Controller equivalent)

│ └── post_handler.go

├── service/ // Business logic layer (Service)

│ └── post_service.go

├── repository/ // Data access layer (Repository)

│ └── post_repository.go

├── model/ // Data model definitions (Model)

│ └── post.go

└── go.mod // Go module settings

Role of each file

-

main.go

Handles application startup and routing configuration. This is the entry point for overall initialization. -

handler/post_handler.go

Contains HTTP request handling tied to routing. Examples: creating posts, retrieving post lists, etc. -

service/post_service.go

Contains business logic. For example, “validation when creating a post” or “toggling between public and private” would go here. -

repository/post_repository.go

Responsible for storage-related operations such as retrieving and saving data. Since we are not using a DB yet, we will manage data in memory and abstract it so that we can swap in a DB later. -

model/post.go

Defines thePoststruct and clarifies the data model that is shared across all layers.

Features to implement (planned)

- Create a post (

POST /posts) - Get a list of posts (

GET /posts) - Get post details (

GET /posts/:id)

You can also add editing, deletion, draft saving, toggling publish status, etc., as needed.

Based on this structure, next we will create main.go and set up server startup and routing. We will continue with a focus on a “simple yet easily extensible design.”

Starting a minimal Gin server

First, let’s run a minimal Web server using Gin. Instead of aiming for full functionality from the start, it’s smoother later on if you first confirm that you have a “working state.”

Installing Go and Gin

Create a project directory and initialize a Go module.

mkdir go-gin-blog-api

cd go-gin-blog-api

go mod init go-gin-blog-api

Install Gin:

go get github.com/gin-gonic/gin

Write the following code in main.go.

package main

import (

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

)

func main() {

r := gin.Default()

r.GET("/health", func(c *gin.Context) {

c.JSON(200, gin.H{

"status": "ok",

})

})

r.Run(":8080") // Start on port 8080

}

Start the server:

go run main.go

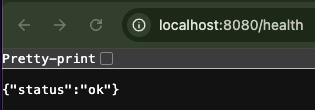

After startup, if you access http://localhost:8080/health, you will get the following JSON response:

{"status":"ok"}

Note: Why use /health?

Endpoints like this are often used for “health checks” and are useful in production environments to check the API’s running status from the outside.

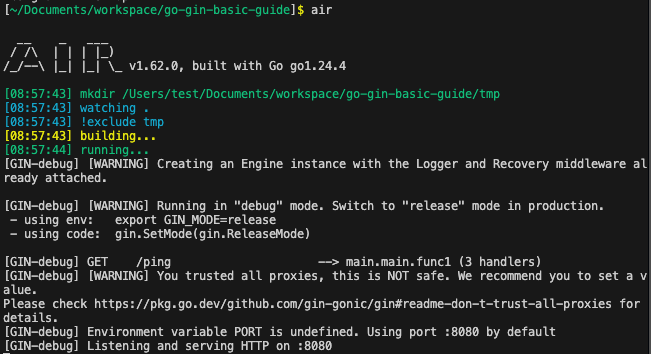

Enabling hot reload with Air

Manually re-running go run main.go every time you change code during development is a subtle but real hassle. A handy tool that automates this is air. With Air, the server will automatically rebuild and restart when code changes.

Install air with the following command:

go install github.com/air-verse/air@latest

After installation, a binary will be added to $GOPATH/bin. If this directory is not in your PATH, add the following to .zshrc or .bashrc:

export PATH="$(go env GOPATH)/bin:$PATH"

Restart your terminal or reload with source ~/.zshrc, etc., then check with:

air -v

air can use a configuration file named .air.toml. Create it in the project root with the following content:

root = "."

tmp_dir = "tmp"

[build]

cmd = "go build -o ./tmp/main main.go"

bin = "tmp/main"

full_bin = "tmp/main"

include_ext = ["go"]

exclude_dir = ["vendor"]

exclude_file = []

delay = 1000

stop_on_error = true

[log]

time = true

[color]

main = "yellow"

Key points:

- Output the temporarily built executable to

tmp_dir - Build the executable binary with

build.cmd - The file specified in

binis executed each time (equivalent to a normalgo run)

Run the following command and Air will watch for source code changes and restart immediately:

air

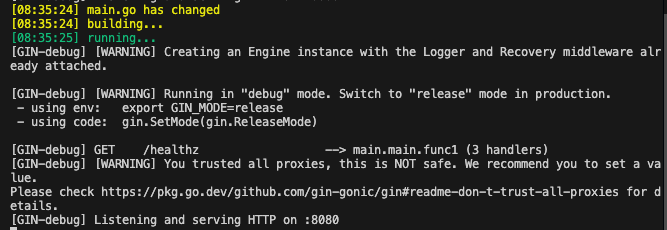

Verifying it works

Edit and save a file; if you see logs like the following in the terminal, it’s working:

main.go has changed

Restarting

Running tmp/main

Note: Why tmp/main?

Air internally runs go build to generate a binary and then executes it. The output destination is tmp/main. This enables faster restarts than go run.

By introducing Air, development efficiency improves significantly. From here on, simply editing and saving code will automatically restart the server, making the feedback loop for checking behavior very smooth.

Next, we’ll define the model for blog post data and gradually implement the API. Let’s proceed step by step in an organized way.

Defining the blog post model (Post)

When designing an API, it’s important to first clarify the data structures you will handle. Since we’re building functionality to create and retrieve blog posts, we’ll define a struct called Post.

Write the following code in model/post.go:

package model

type Post struct {

ID string `json:"id"` // Post ID

Title string `json:"title"` // Title

Content string `json:"content"` // Body

Author string `json:"author"` // Author name

}

This struct will be used in common across the service and handler layers.

Meaning of the JSON tags

The json:"..." tags on each field specify the names used when Gin serializes and deserializes requests and responses as JSON.

For example, the following JSON sent to the /posts endpoint will be mapped to this struct:

{

"id": "1",

"title": "Getting Started with Gin",

"content": "Gin is a lightweight web framework for Go.",

"author": "Gopher"

}

With this Post model at the center, next we’ll design API routing for “creating posts” and “retrieving post lists” and implement the Gin handler layer.

Creating and retrieving posts: implementing handlers

Using the Post model, we’ll implement endpoints that actually register and retrieve blog posts. Here we’ll create handlers for the following two operations:

POST /posts: Create a new postGET /posts: Retrieve a list of posts

Write the following code in handler/post_handler.go:

package handler

import (

"go-gin-blog-api/model"

"net/http"

"sync"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

)

// Simple in-memory storage (normally you would use a DB)

var (

posts = []model.Post{}

mutex = &sync.Mutex{}

)

func RegisterPostRoutes(r *gin.Engine) {

r.POST("/posts", CreatePost)

r.GET("/posts", GetPosts)

}

// Handler for creating a post

func CreatePost(c *gin.Context) {

var newPost model.Post

if err := c.ShouldBindJSON(&newPost); err != nil {

c.JSON(http.StatusBadRequest, gin.H{"error": err.Error()})

return

}

mutex.Lock()

posts = append(posts, newPost)

mutex.Unlock()

c.JSON(http.StatusCreated, newPost)

}

// Handler for retrieving the list of posts

func GetPosts(c *gin.Context) {

mutex.Lock()

defer mutex.Unlock()

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, posts)

}

Code notes

This handler is a simple implementation that allows you to create and list posts in memory without using a DB.

var (

posts = []model.Post{}

mutex = &sync.Mutex{}

)

posts: A slice that holds post data. In a real app, this would be managed by a DB, but here we manage it in memory.mutex: Provides mutual exclusion so that data is not corrupted when multiple requests access it simultaneously.

func CreatePost(c *gin.Context) {

var newPost model.Post

if err := c.ShouldBindJSON(&newPost); err != nil {

c.JSON(http.StatusBadRequest, gin.H{"error": err.Error()})

return

}

mutex.Lock()

posts = append(posts, newPost)

mutex.Unlock()

c.JSON(http.StatusCreated, newPost)

}

c.ShouldBindJSON(&newPost): Binds the posted JSON request tomodel.Post.mutex.Lock()tomutex.Unlock(): Locks to prevent other requests from modifyingpostsat the same time.- On success, returns the posted content with a

201 Createdstatus.

func GetPosts(c *gin.Context) {

mutex.Lock()

defer mutex.Unlock()

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, posts)

}

- A simple implementation that returns the

postsdata as JSON. - A lock is also used for reads to maintain a consistent state.

We will later split this into service and repository layers.

Adding routing to main.go

package main

import (

+ "github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

"go-gin-blog-api/handler"

)

func main() {

r := gin.Default()

r.GET("/healthz", func(c *gin.Context) {

c.JSON(200, gin.H{

"status": "ok",

})

})

+ handler.RegisterPostRoutes(r)

r.Run(":8080") // Start on port 8080

}

Verifying it works

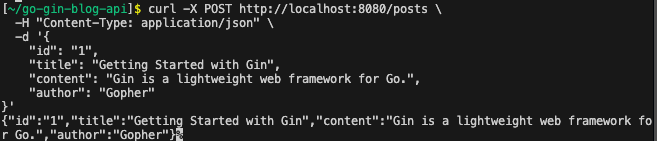

Request to create a post (POST /posts):

curl -X POST http://localhost:8080/posts \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"id": "1",

"title": "Getting Started with Gin",

"content": "Gin is a lightweight web framework for Go.",

"author": "Gopher"

}'

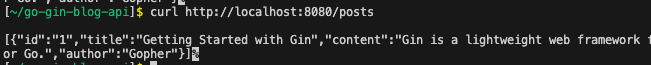

Request to retrieve posts (GET /posts):

curl http://localhost:8080/posts

Note: Persistence is not needed yet

At this stage, we’re using a simple in-memory implementation without a DB. Therefore, any posts you create will be lost when the server restarts. We’ll cover switching to proper persistence (e.g., an RDB) later.

Separating business logic with a service layer

As your app grows, tightly coupling routing and business logic will reduce maintainability. It’s important to separate business logic into a service layer and clarify responsibilities.

Here, we’ll refactor by extracting the create and retrieve operations for posts into a service and calling it from the handler.

Write the following code in service/post_service.go:

package service

import (

"go-gin-blog-api/model"

"sync"

)

type PostService interface {

Create(post model.Post) model.Post

List() []model.Post

}

type postService struct {

mu sync.Mutex

posts []model.Post

}

func NewPostService() PostService {

return &postService{

posts: make([]model.Post, 0),

}

}

func (s *postService) Create(post model.Post) model.Post {

s.mu.Lock()

defer s.mu.Unlock()

s.posts = append(s.posts, post)

return post

}

func (s *postService) List() []model.Post {

s.mu.Lock()

defer s.mu.Unlock()

return append([]model.Post(nil), s.posts...)

}

Code explanation:

type PostService interface {

Create(post model.Post) model.Post

List() []model.Post

}

PostServiceinterface: Defines the functions (i.e., contract) provided by the service layer.- This makes it easier to test and to swap implementations in the future (dependency abstraction).

type postService struct {

mu sync.Mutex

posts []model.Post

}

postServicestruct: The actual implementation.posts: Holds the list of posts (in memory for now, not in a DB).mu: A mutex for mutual exclusion to handle concurrent access from multiple requests.

func (s *postService) Create(post model.Post) model.Post {

s.mu.Lock()

defer s.mu.Unlock()

s.posts = append(s.posts, post)

return post

}

- Adds the post to the slice.

- The

Lock→Unlockflow makes the processing thread-safe (safe under concurrency).

func (s *postService) List() []model.Post {

s.mu.Lock()

defer s.mu.Unlock()

return append([]model.Post(nil), s.posts...)

}

- Returns the list of posts.

Next, update handler/post_handler.go to match the service layer implementation.

(Diffs omitted)

package handler

import (

"go-gin-blog-api/model"

"go-gin-blog-api/service"

"net/http"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

)

type PostHandler struct {

postService service.PostService

}

func NewPostHandler(s service.PostService) *PostHandler {

return &PostHandler{postService: s}

}

func (h *PostHandler) RegisterRoutes(r *gin.Engine) {

r.POST("/posts", h.CreatePost)

r.GET("/posts", h.GetPosts)

}

func (h *PostHandler) CreatePost(c *gin.Context) {

var newPost model.Post

if err := c.ShouldBindJSON(&newPost); err != nil {

c.JSON(http.StatusBadRequest, gin.H{"error": err.Error()})

return

}

created := h.postService.Create(newPost)

c.JSON(http.StatusCreated, created)

}

func (h *PostHandler) GetPosts(c *gin.Context) {

posts := h.postService.List()

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, posts)

}

Code explanation:

type PostHandler struct {

postService service.PostService

}

- The handler is the layer that receives HTTP requests.

- The key point is that it does not hold business logic; instead, it delegates processing to the service layer.

func NewPostHandler(s service.PostService) *PostHandler {

return &PostHandler{postService: s}

}

- This is the DI (Dependency Injection) pattern.

- It makes the structure easier to test because you can pass a mock service during testing.

func (h *PostHandler) CreatePost(c *gin.Context) {

var newPost model.Post

if err := c.ShouldBindJSON(&newPost); err != nil {

c.JSON(http.StatusBadRequest, gin.H{"error": err.Error()})

return

}

created := h.postService.Create(newPost)

c.JSON(http.StatusCreated, created)

}

- Maps (binds) JSON to

model.Post. - Returns 400 if there is an error.

- Delegates processing to the service and returns the result as JSON.

func (h *PostHandler) GetPosts(c *gin.Context) {

posts := h.postService.List()

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, posts)

}

- Retrieves the list of posts and returns it as is.

Update main.go:

package main

import (

"go-gin-blog-api/handler"

+ "go-gin-blog-api/service"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

)

func main() {

r := gin.Default()

r.GET("/health", func(c *gin.Context) {

c.JSON(200, gin.H{"status": "ok"})

})

- handler.RegisterPostRoutes(r)

+ postService := service.NewPostService()

+ postHandler := handler.NewPostHandler(postService)

+ postHandler.RegisterRoutes(r)

r.Run(":8080")

}

After rewriting the code, verify that everything works.

Check that you can successfully create blog posts and retrieve the list of posts.

Designing and implementing the repository layer

Once the service layer is in place, the next step is to implement the “repository layer.”

The repository layer is responsible for persistence and abstracts storage handling such as databases, files, or memory. This allows the application’s business logic (service layer) to handle data without caring where it is stored.

Reconfirming the directory structure

go-gin-blog-api/

├── model/

│ └── post.go

├── repository/

│ └── post_repository.go 👈 Here!

├── service/

│ └── post_service.go

├── handler/

│ └── post_handler.go

├── main.go

package repository

import (

"go-gin-blog-api/model"

"sync"

)

type PostRepository interface {

Save(post model.Post) model.Post

FindAll() []model.Post

}

type postRepository struct {

mu sync.Mutex

posts []model.Post

}

func NewPostRepository() PostRepository {

return &postRepository{

posts: make([]model.Post, 0),

}

}

func (r *postRepository) Save(post model.Post) model.Post {

r.mu.Lock()

defer r.mu.Unlock()

r.posts = append(r.posts, post)

return post

}

func (r *postRepository) FindAll() []model.Post {

r.mu.Lock()

defer r.mu.Unlock()

return append([]model.Post(nil), r.posts...)

}

Code explanation:

PostRepositoryinterface- Defines the operations (save, retrieve) provided by the repository.

- This makes it easy to switch to a DB or external API later (interface-driven design).

postRepositorystruct- Currently holds data in memory as

posts []model.Post. - When switching to an RDB or NoSQL in the future, you only need to replace the internals of this struct.

- Currently holds data in memory as

- Synchronization

- Uses

sync.Mutexfor mutual exclusion so that data is not corrupted even if multiple requests post at the same time.

- Uses

Why is the repository layer important?

| Reason | Description |

|---|---|

| Separation of concerns | Keeps the service layer simple by separating data operation logic |

| Testability | Easy to mock, making unit tests for the service layer simple |

| Flexible extensibility | When switching to a DB connection, the impact range is small |

Next, update the service layer to use the repository.

package service

import (

"go-gin-blog-api/model"

"go-gin-blog-api/repository"

)

type PostService interface {

Create(post model.Post) model.Post

List() []model.Post

}

type postService struct {

repo repository.PostRepository

}

func NewPostService(r repository.PostRepository) PostService {

return &postService{repo: r}

}

func (s *postService) Create(post model.Post) model.Post {

return s.repo.Save(post)

}

func (s *postService) List() []model.Post {

return s.repo.FindAll()

}

PostService: Interface for the service layer.postService: Implementation struct. It manipulates data through the repository.- Although the business logic is simple for now, future additions such as validation or logging can be consolidated in this layer.

Finally, update main.go:

package main

import (

"go-gin-blog-api/handler"

+ "go-gin-blog-api/repository"

"go-gin-blog-api/service"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

)

func main() {

r := gin.Default()

r.GET("/health", func(c *gin.Context) {

c.JSON(200, gin.H{"status": "ok"})

})

+ postRepo := repository.NewPostRepository()

- postService := service.NewPostService()

+ postService := service.NewPostService(postRepo)

postHandler := handler.NewPostHandler(postService)

postHandler.RegisterRoutes(r)

r.Run(":8080")

}

- All dependencies are injected in

main.go(dependency injection). - This makes each layer loosely coupled and easier to test or swap out.

RegisterRoutescentralizes routing definitions inhandler, keepingmain.goclean and easy to read.

Adding retrieve, update, and delete operations for posts

So far, we’ve implemented listing and creating posts. Next, we’ll take one more step toward a full-fledged blog API by adding functionality to retrieve, update, and delete posts.

API endpoints

We’ll add the following three RESTful APIs:

| Method | Path | Description |

|---|---|---|

GET |

/posts/:id |

Retrieve a post with the given ID |

PATCH |

/posts/:id |

Partially update a post (e.g., title) |

DELETE |

/posts/:id |

Delete a post |

Extending the repository layer

In the repository layer, we’ll enable the following operations on in-memory data:

- Retrieve a single post by ID:

FindByID - Partially update a post:

Update - Delete a post:

Delete

func (r *postRepository) FindByID(id string) (*model.Post, bool) {

for _, post := range r.posts {

if post.ID == id {

return &post, true

}

}

return nil, false

}

func (r *postRepository) Update(id string, updated model.Post) (*model.Post, bool) {

for i, post := range r.posts {

if post.ID == id {

if updated.Title != "" {

r.posts[i].Title = updated.Title

}

if updated.Content != "" {

r.posts[i].Content = updated.Content

}

if updated.Author != "" {

r.posts[i].Author = updated.Author

}

return &r.posts[i], true

}

}

return nil, false

}

func (r *postRepository) Delete(id string) bool {

for i, post := range r.posts {

if post.ID == id {

r.posts = append(r.posts[:i], r.posts[i+1:]...)

return true

}

}

return false

}

Update the interface as well:

type PostRepository interface {

Create(post model.Post) model.Post

FindAll() []model.Post

+ FindByID(id string) (*model.Post, bool)

+ Update(id string, updated model.Post) (*model.Post, bool)

+ Delete(id string) bool

}

Updating the service layer

In the service layer, we’ll add methods that wrap repository operations:

func (s *postService) GetByID(id string) (*model.Post, bool) {

return s.repo.FindByID(id)

}

func (s *postService) Update(id string, post model.Post) (*model.Post, bool) {

return s.repo.Update(id, post)

}

func (s *postService) Delete(id string) bool {

return s.repo.Delete(id)

}

Update the interface as well:

type PostService interface {

Create(post model.Post) model.Post

GetAll() []model.Post

+ GetByID(id string) (*model.Post, bool)

+ Update(id string, updated model.Post) (*model.Post, bool)

+ Delete(id string) bool

}

Implementing the handlers

Now define the actual request handling in the handler layer.

func (h *PostHandler) RegisterRoutes(r *gin.Engine) {

r.POST("/posts", h.CreatePost)

r.GET("/posts", h.GetPosts)

+ r.GET("/posts/:id", h.GetPostByID)

+ r.PATCH("/posts/:id", h.UpdatePost)

+ r.DELETE("/posts/:id", h.DeletePost)

}

Handlers for each endpoint are as follows:

func (h *PostHandler) GetPostByID(c *gin.Context) {

id := c.Param("id")

post, found := h.postService.GetByID(id)

if !found {

c.JSON(http.StatusNotFound, gin.H{"error": "Post not found"})

return

}

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, post)

}

func (h *PostHandler) UpdatePost(c *gin.Context) {

id := c.Param("id")

var update model.Post

if err := c.ShouldBindJSON(&update); err != nil {

c.JSON(http.StatusBadRequest, gin.H{"error": err.Error()})

return

}

post, updated := h.postService.Update(id, update)

if !updated {

c.JSON(http.StatusNotFound, gin.H{"error": "Post not found"})

return

}

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, post)

}

func (h *PostHandler) DeletePost(c *gin.Context) {

id := c.Param("id")

if deleted := h.postService.Delete(id); !deleted {

c.JSON(http.StatusNotFound, gin.H{"error": "Post not found"})

return

}

c.Status(http.StatusNoContent)

}

Verifying behavior with curl

You can check the API behavior with the following curl commands.

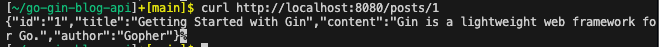

Retrieve a single post:

curl http://localhost:8080/posts/1

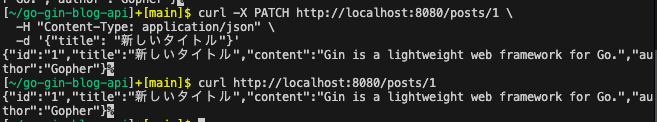

Partially update a post:

curl -X PATCH http://localhost:8080/posts/1 \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"title": "New title"}'

Delete a post:

curl -X DELETE http://localhost:8080/posts/1

Conclusion

Up to this point, we have gone through the basic process of building a blog post API with an MVC structure using Go × Gin.

- Starting from Gin’s minimal setup

- Separating layers into model, service, and repository

- Organizing handlers and defining routing

- Step-by-step implementation of basic APIs for creating, retrieving, updating, and deleting posts

In this implementation, data management is still limited to in-memory storage, and more preparation is needed for real-world operation. In actual development, you need connections to a persistent database, robust validation logic, and above all, solid tests.

In the next article, we will cover:

- A practical guide to robust test design and implementation with Go × Gin × MVC

- Separation and strategy for unit tests and integration tests

- How to write tests using mocks

- Near-E2E testing of Gin apps using

httptestandtestify

Through introducing tests and persistence, we’ll explore API design that you can safely evolve over time.

Questions about this article 📝

If you have any questions or feedback about the content, please feel free to contact us.Go to inquiry form

Related Articles

Complete Cache Strategy Guide: Maximizing Performance with CDN, Redis, and API Optimization

2024/03/07Getting Started with Building Web Servers Using Go × Echo: Learn Simple, High‑Performance API Development in the Shortest Time

2023/12/03Go × Gin Advanced: Practical Techniques and Scalable API Design

2023/11/29Go × Gin Basics: A Thorough Guide to Building a High-Speed API Server

2023/11/23Article & Like API with Go + Gin + GORM (Part 1): First, an "implementation-first controller" with all-in-one CRUD

2025/07/13Robust Test Design and Implementation Guide in a Go × Gin × MVC Architecture

2023/12/04Bringing a Go + Gin App Up to Production Quality: From Configuration and Structure to CI

2023/12/06Released a string slice utility for Go: “strlistutils”

2025/06/19