Go × Gin Advanced: Practical Techniques and Scalable API Design

This post is also available in .

Introduction

Once you’ve mastered the basics of Go × Gin, it’s time to move on to the next step.

In this advanced guide, we’ll summarize techniques that are useful in real API development, along with design tips for building scalable systems in the future.

Specifically, we’ll cover topics like:

- Implementation examples of authentication and validation

- Error-handling patterns

- Testing methods for Gin applications

- How to create custom middleware

- Outlook on scalable API design

With these in mind, we’ll further strengthen your foundational skills so you won’t get stuck in real projects.

If you want to learn the basics of Gin, see this article:

Useful Gin Features You’ll Use Often

Binding

Gin can map (bind) request parameters to structs.

Below is an example of binding query parameters to a struct.

type QueryParams struct {

Name string `form:"name"`

Age int `form:"age"`

}

r.GET("/bind", func(c *gin.Context) {

var params QueryParams

if err := c.ShouldBindQuery(¶ms); err != nil {

c.JSON(400, gin.H{"error": err.Error()})

return

}

c.JSON(200, gin.H{"name": params.Name, "age": params.Age})

})

curl 'http://localhost:8080/bind?name=Gopher'

Response

{"age":0,"name":"Gopher"}

Validation

Gin can also perform validation using binding tags.

type User struct {

Name string `json:"name" binding:"required"`

Age int `json:"age" binding:"gte=0,lte=120"`

}

r.POST("/validate", func(c *gin.Context) {

var user User

if err := c.ShouldBindJSON(&user); err != nil {

c.JSON(400, gin.H{"error": err.Error()})

return

}

c.JSON(200, gin.H{"name": user.Name, "age": user.Age})

})

binding:"required"→ required checkbinding:"gte=0,lte=120"→ checks that the value is between 0 and 120 inclusive

Request

curl -X POST http://localhost:8080/validate \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"name": "Gopher", "age": 5}'

Response

{"age":5,"name":"Gopher"}

Request (change age to a value outside the range)

curl -X POST http://localhost:8080/validate \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"name": "Gopher", "age": 999}'

Response

{"error":"Key: 'User.Age' Error:Field validation for 'Age' failed on the 'lte' tag"}

Creating a Custom Validator

If the standard validation is not enough, you can register your own validation logic.

package main

import (

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

"github.com/go-playground/validator/v10"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin/binding"

)

func main() {

r := gin.Default()

// Register custom validation

if v, ok := binding.Validator.Engine().(*validator.Validate); ok {

v.RegisterValidation("customTag", customValidation)

}

r.POST("/custom", func(c *gin.Context) {

var user User

if err := c.ShouldBindJSON(&user); err != nil {

c.JSON(400, gin.H{"error": err.Error()})

return

}

c.JSON(200, gin.H{"name": user.Name})

})

r.Run()

}

type User struct {

Name string `json:"name" binding:"required,customTag"`

}

// Custom validation function

func customValidation(fl validator.FieldLevel) bool {

value := fl.Field().String()

return len(value) >= 3 // passes if length is 3 or more

}

Request

curl -X POST http://localhost:8080/custom \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"name":"Gopher"}'

Response

{"name":"Gopher"}

Request (example that does not meet the condition: “less than 3 characters”)

curl -X POST http://localhost:8080/custom \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"name":"Go"}'

Response

{"error":"Key: 'User.Name' Error:Field validation for 'Name' failed on the 'customTag' tag"}

Designing Structured Handlers

As you progress with API development using Gin, structuring your handlers becomes increasingly important.

Here we’ll look at ways of making handlers loosely coupled and easy to maintain, along with a basic example of dependency injection.

Why Structure Is Necessary

If you keep writing handlers as plain func(c *gin.Context), you’ll run into issues like:

- Growing dependencies on database connections and external services

- Hard-to-test code

- Reduced readability

By grouping handlers into structs and separating business logic into a service layer, you can prevent these problems.

What Is the Service Layer?

The service layer is the part that handles the application’s business logic.

As a concrete example, it’s common to define a UserService interface that deals with user information.

type UserService interface {

GetByID(id string) (User, error)

}

Example of a Struct-Based Handler

Handlers are initialized by injecting dependencies on the service layer.

type UserHandler struct {

userService UserService

}

func NewUserHandler(service UserService) *UserHandler {

return &UserHandler{userService: service}

}

func (h *UserHandler) GetUser(c *gin.Context) {

id := c.Param("id")

user, err := h.userService.GetByID(id)

if err != nil {

c.JSON(404, gin.H{"error": "User not found"})

return

}

c.JSON(200, user)

}

In this example, the handler delegates work to UserService, and the core processing is moved into the service layer.

Using It in Routing

When actually using it in routing, you wire up and pass the dependencies.

// Example: main.go

repo := NewUserRepository()

userService := NewUserService(repo)

userHandler := NewUserHandler(userService)

r.GET("/users/:id", userHandler.GetUser)

- UserRepository: responsible for data access

- UserService: responsible for business logic

- UserHandler: responsible for HTTP interactions

Separating them like this clarifies each role.

Benefits of Structuring

- Dependencies become explicit and the code is easier to understand

- It’s easier to inject mocks, making testing simpler

- Easier to maintain and extend by responsibility

Supplement: Implementation Example

Below is an implementation that reflects the above concept in actual code.

Directory structure (example)

go-gin-test-guide/

├── main.go

├── handler/

│ └── user_handler.go

├── service/

│ └── user_service.go

├── repository/

│ └── user_repository.go

└── model/

└── user.go

package model

type User struct {

ID string `json:"id"`

Name string `json:"name"`

}

package repository

import "my-gin-app/model"

type UserRepository interface {

FindByID(id string) (*model.User, error)

}

type userRepositoryImpl struct {

// In a real app this would hold DB connections, etc., but omitted here

}

func NewUserRepository() UserRepository {

return &userRepositoryImpl{}

}

func (r *userRepositoryImpl) FindByID(id string) (*model.User, error) {

// As an example, return static user information

if id == "1" {

return &model.User{ID: "1", Name: "Gopher"}, nil

}

return nil, nil // When not found

}

package service

import (

"errors"

"my-gin-app/model"

"my-gin-app/repository"

)

type UserService interface {

GetByID(id string) (*model.User, error)

}

type userServiceImpl struct {

repo repository.UserRepository

}

func NewUserService(repo repository.UserRepository) UserService {

return &userServiceImpl{repo: repo}

}

func (s *userServiceImpl) GetByID(id string) (*model.User, error) {

user, err := s.repo.FindByID(id)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

if user == nil {

return nil, errors.New("user not found")

}

return user, nil

}

package handler

import (

"net/http"

"my-gin-app/service"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

)

type UserHandler struct {

userService service.UserService

}

func NewUserHandler(service service.UserService) *UserHandler {

return &UserHandler{userService: service}

}

func (h *UserHandler) GetUser(c *gin.Context) {

id := c.Param("id")

user, err := h.userService.GetByID(id)

if err != nil {

c.JSON(http.StatusNotFound, gin.H{"error": "User not found"})

return

}

c.JSON(http.StatusOK, user)

}

package main

import (

"my-gin-app/handler"

"my-gin-app/repository"

"my-gin-app/service"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

)

func main() {

r := gin.Default()

userRepo := repository.NewUserRepository()

userService := service.NewUserService(userRepo)

userHandler := handler.NewUserHandler(userService)

// Routing

r.GET("/users/:id", userHandler.GetUser)

r.Run(":8080")

}

Request (when the user is found)

curl http://localhost:8080/users/1

Response

{"id":"1","name":"Gopher"}

Request

curl http://localhost:8080/users/999

Response

{"error":"User not found"}

Testing Methods

For API development with Gin, it’s robust to design tests across the following three layers:

- Handler tests

- Service layer / repository layer tests

- Integration tests

Below is a summary of each testing method with sample code.

Handler Tests

When testing Gin handlers, keep the following in mind:

- Use

httptest.NewRecorderto simulate actual HTTP requests - Mock dependent services or repositories as needed (in this example, we mock the service)

Defining a Mock

First, we mock service.UserService.

This allows us to test only the behavior of the handler.

package handler_test

import (

"errors"

"go-gin-basic-guide/handler"

"go-gin-basic-guide/model"

"net/http"

"net/http/httptest"

"testing"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

"github.com/stretchr/testify/assert"

)

// Mock service

type mockUserService struct {

getByIDFunc func(id string) (*model.User, error)

}

func (m *mockUserService) GetByID(id string) (*model.User, error) {

return m.getByIDFunc(id)

}

Handler Test Code

We’ll actually test the /users/:id endpoint.

func TestGetUser_Success(t *testing.T) {

// Set Gin to test mode

gin.SetMode(gin.TestMode)

// Prepare mock service

mockService := &mockUserService{

getByIDFunc: func(id string) (*model.User, error) {

return &model.User{ID: id, Name: "Test User"}, nil

},

}

// Create handler

userHandler := handler.NewUserHandler(mockService)

// Register handler with Gin router

r := gin.Default()

r.GET("/users/:id", userHandler.GetUser)

// Create request

req, _ := http.NewRequest("GET", "/users/1", nil)

w := httptest.NewRecorder()

// Execute request

r.ServeHTTP(w, req)

// Verify result

assert.Equal(t, http.StatusOK, w.Code)

assert.JSONEq(t, `{"id":"1","name":"Test User"}`, w.Body.String())

}

func TestGetUser_NotFound(t *testing.T) {

gin.SetMode(gin.TestMode)

mockService := &mockUserService{

getByIDFunc: func(id string) (*model.User, error) {

return nil, errors.New("user not found")

},

}

userHandler := handler.NewUserHandler(mockService)

r := gin.Default()

r.GET("/users/:id", userHandler.GetUser)

req, _ := http.NewRequest("GET", "/users/999", nil)

w := httptest.NewRecorder()

r.ServeHTTP(w, req)

assert.Equal(t, http.StatusNotFound, w.Code)

assert.JSONEq(t, `{"error":"User not found"}`, w.Body.String())

}

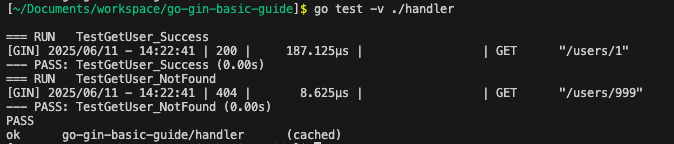

Run tests

go test -v ./handler

The tests completed successfully.

Finally, as a refactor, we’ll create a common router initialization function for tests.

func setupRouter(handlerFunc gin.HandlerFunc) *gin.Engine {

gin.SetMode(gin.TestMode)

r := gin.Default()

r.GET("/users/:id", handlerFunc)

return r

}

func TestGetUser_Success(t *testing.T) {

mockService := &mockUserService{

getByIDFunc: func(id string) (*model.User, error) {

return &model.User{ID: id, Name: "Test User"}, nil

},

}

userHandler := handler.NewUserHandler(mockService)

r := setupRouter(userHandler.GetUser)

req, _ := http.NewRequest("GET", "/users/1", nil)

w := httptest.NewRecorder()

r.ServeHTTP(w, req)

assert.Equal(t, http.StatusOK, w.Code)

assert.JSONEq(t, `{"id":"1","name":"Test User"}`, w.Body.String())

}

func TestGetUser_NotFound(t *testing.T) {

mockService := &mockUserService{

getByIDFunc: func(id string) (*model.User, error) {

return nil, errors.New("user not found")

},

}

userHandler := handler.NewUserHandler(mockService)

r := setupRouter(userHandler.GetUser)

req, _ := http.NewRequest("GET", "/users/999", nil)

w := httptest.NewRecorder()

r.ServeHTTP(w, req)

assert.Equal(t, http.StatusNotFound, w.Code)

assert.JSONEq(t, `{"error":"User not found"}`, w.Body.String())

}

When the number of test patterns increases, such common functions become necessary.

Service Layer Tests

In service layer tests, you mock the repository and verify only the business logic.

Here is an example test for service/user_service.go.

package service_test

import (

"go-gin-basic-guide/model"

"go-gin-basic-guide/service"

"testing"

"github.com/stretchr/testify/assert"

)

// Repository mock

type mockUserRepo struct {

findByIDFunc func(id string) (*model.User, error)

}

func (m *mockUserRepo) FindByID(id string) (*model.User, error) {

return m.findByIDFunc(id)

}

func TestGetByID_Success(t *testing.T) {

repo := &mockUserRepo{

findByIDFunc: func(id string) (*model.User, error) {

return &model.User{ID: id, Name: "Mock User"}, nil

},

}

userService := service.NewUserService(repo)

user, err := userService.GetByID("1")

assert.NoError(t, err)

assert.Equal(t, "Mock User", user.Name)

}

func TestGetByID_NotFound(t *testing.T) {

repo := &mockUserRepo{

findByIDFunc: func(id string) (*model.User, error) {

return nil, nil

},

}

userService := service.NewUserService(repo)

user, err := userService.GetByID("999")

assert.Nil(t, user)

assert.EqualError(t, err, "user not found")

}

✅ Key points

- In the service layer, focus tests on business-logic-related condition branches

- Data access is mocked (no dependency on the repository layer)

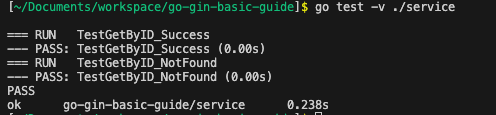

Run tests

go test -v ./service

Repository Layer Tests

In the repository layer, you often use a real DB (e.g., SQLite or a test MySQL) or an in-memory DB.

For small cases, you might use table mocks.

Example (simplified concept):

func TestFindByID_RealDB(t *testing.T) {

db := setupTestDB() // Example: initialize an in-memory SQLite DB

repo := repository.NewUserRepositoryWithDB(db)

// Create test data beforehand

db.Exec("INSERT INTO users (id, name) VALUES (?, ?)", "1", "Test User")

user, err := repo.FindByID("1")

assert.NoError(t, err)

assert.Equal(t, "Test User", user.Name)

}

Integration Tests

These are tests where you actually start a server and verify API requests and responses.

By using httptest.NewServer, you can start the server in a way that’s close to production and test it.

package integration_test

import (

"go-gin-basic-guide/handler"

"go-gin-basic-guide/repository"

"go-gin-basic-guide/service"

"net/http"

"net/http/httptest"

"testing"

"github.com/gin-gonic/gin"

"github.com/stretchr/testify/assert"

)

// Set up test server

func setupIntegrationRouter() *gin.Engine {

repo := repository.NewUserRepository()

userService := service.NewUserService(repo)

userHandler := handler.NewUserHandler(userService)

r := gin.Default()

r.GET("/users/:id", userHandler.GetUser)

return r

}

func TestGetUserIntegration_Success(t *testing.T) {

gin.SetMode(gin.TestMode)

r := setupIntegrationRouter()

ts := httptest.NewServer(r)

defer ts.Close()

resp, err := http.Get(ts.URL + "/users/1")

assert.NoError(t, err)

assert.Equal(t, http.StatusOK, resp.StatusCode)

// Also verify response body

defer resp.Body.Close()

body := make([]byte, resp.ContentLength)

resp.Body.Read(body)

assert.JSONEq(t, `{"id":"1","name":"Gopher"}`, string(body))

}

func TestGetUserIntegration_NotFound(t *testing.T) {

gin.SetMode(gin.TestMode)

r := setupIntegrationRouter()

ts := httptest.NewServer(r)

defer ts.Close()

resp, err := http.Get(ts.URL + "/users/999")

assert.NoError(t, err)

assert.Equal(t, http.StatusNotFound, resp.StatusCode)

defer resp.Body.Close()

body := make([]byte, resp.ContentLength)

resp.Body.Read(body)

assert.JSONEq(t, `{"error":"User not found"}`, string(body))

}

✅ Key points

- Start a Gin server and send actual HTTP requests

- Dependencies are real implementations, so you test end-to-end across service and repository layers

- The scope is narrower than full E2E (including external integrations), but it’s ideal for “internal application integration checks”

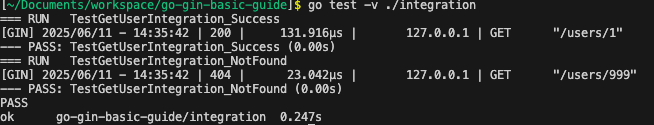

Run tests

go test -v ./integration

Techniques for Using Gin Grouping and Routing

Versioning

Organizing common paths/authentication rules

Error-Handling Patterns

Standardizing error responses

Leveraging Gin’s Error type

Authentication and Authorization Implementation Examples

JWT authentication

Implementation as middleware

Toward More Scalable Design

Steps toward service decomposition and microservices

Future architectural outlook

Summary and Review

Questions about this article 📝

If you have any questions or feedback about the content, please feel free to contact us.Go to inquiry form

Related Articles

Complete Cache Strategy Guide: Maximizing Performance with CDN, Redis, and API Optimization

2024/03/07Getting Started with Building Web Servers Using Go × Echo: Learn Simple, High‑Performance API Development in the Shortest Time

2023/12/03Go × Gin Basics: A Thorough Guide to Building a High-Speed API Server

2023/11/23Article & Like API with Go + Gin + GORM (Part 1): First, an "implementation-first controller" with all-in-one CRUD

2025/07/13Building an MVC-Structured Blog Post Web API with Go × Gin: From Basics to Scalable Design

2023/12/03Robust Test Design and Implementation Guide in a Go × Gin × MVC Architecture

2023/12/04Bringing a Go + Gin App Up to Production Quality: From Configuration and Structure to CI

2023/12/06Released a string slice utility for Go: “strlistutils”

2025/06/19