Implementing Essential UI Component Tests for Frontend Development with React Testing Library

This post is also available in .

Introduction

In automated frontend testing, UI component tests are probably something you always encounter.

In particular, components that are shared and used across many screens are often subject to frequent changes.

Manually checking every screen each time to ensure that existing pages are not affected when something is changed is a huge amount of work.

There are many situations where it’s better to add automated tests for UI components to ensure that the DOM is rendered as before and that event behavior such as onClick and onChange has not changed.

In React, React Testing Library is commonly used as the de facto tool for this.

I’ll introduce automated testing of UI components by walking through how to set up React Testing Library and how to use it with simple examples.

What is React Testing Library?

React Testing Library is a library for testing React components.

It focuses on testing from the user’s perspective, allowing you to write tests that are close to real usage scenarios without depending on implementation details of the components.

The goal of this library is to make tests less sensitive to changes in application code so that they are easier to maintain and closer to production behavior.

More concretely, React Testing Library has the following characteristics:

-

Focus on user interaction:

You can write tests as if a user is operating the application, verifying that the UI responds as expected through button clicks and input operations. -

Independent of implementation details:

Tests are based on elements and text rendered in the DOM, so they are less likely to break even if the implementation changes slightly. -

Accessibility-friendly:

It provides queries such as getByRole, making it easier to write tests that take accessibility into account. This allows you to obtain DOM elements in a way that is closer to how real users interact with them. -

Easy to combine with Jest:

By using it together with testing frameworks such as Jest, you can improve the overall test coverage of your React application.

Goal of this article

We’ll refer to the official React Testing Library documentation to set it up and write some simple test code.

In the end, we’ll implement tests for interactive UI components that receive user actions (events) in a component.

describe('Search', () => {

it('renders Search component', () => {

render(<Search />)

fireEvent.change(screen.getByRole('textbox'), {

target: { value: 'Next.js' },

})

waitFor(() =>

expect(

screen.getByText(/Searches for JavaScript/)

).toBeInTheDocument()

)

})

})

Preparation for introducing React Testing Library

To introduce React Testing Library, we first need an environment where React components can run.

You could install each library one by one, but to get as close as possible to a real-world development environment, we’ll set up Next.js.

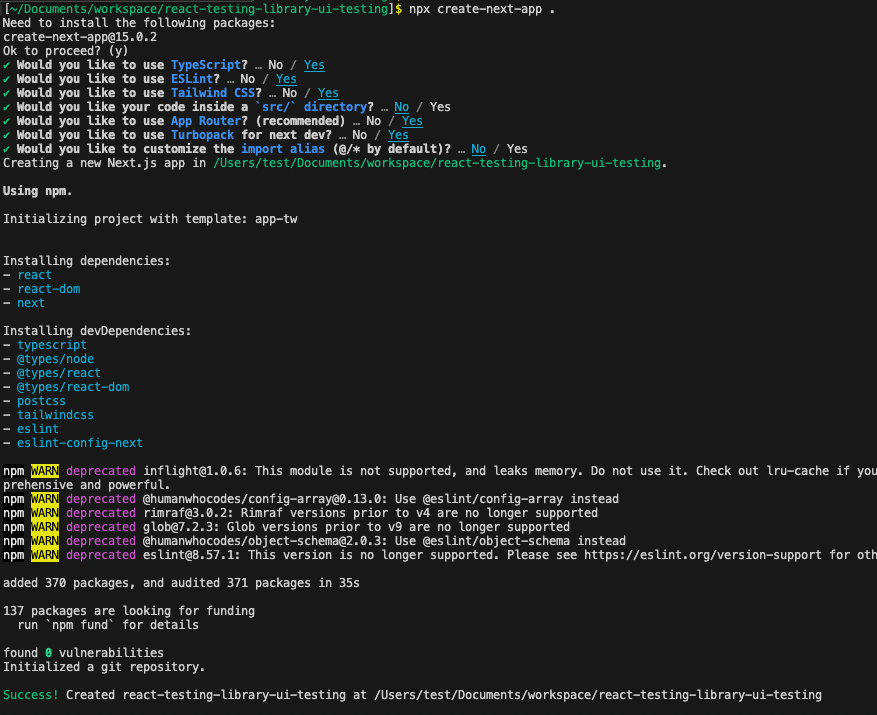

Create an appropriate folder and set it up with create-next-app.

mkdir react-testing-library-ui-testing

cd react-testing-library-ui-testing

npx create-next-app@14.2.2 .

Once setup is complete, make sure that Next.js can be started locally.

npm run dev

Setting up Jest

React Testing Library itself can work not only with Jest but also with Vitest and others, but here we’ll use Jest.

Install the required packages all at once.

npm install --save-dev jest ts-jest ts-node @types/jest jest-environment-jsdom

After installation, we’ll check that Jest runs correctly.

Jest configuration

First, create a jest.config.ts file and configure it.

import type {Config} from 'jest';

const config: Config = {

clearMocks: true,

coverageProvider: "v8",

preset: "ts-jest",

testEnvironment: "jest-environment-jsdom",

};

export default config;

Add a script to package.json to run Jest.

"scripts": {

"dev": "next dev",

"build": "next build",

"start": "next start",

- "lint": "next lint"

+ "lint": "next lint",

+ "test": "jest"

},

"dependencies": {

Sample test code

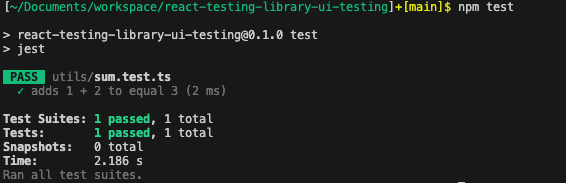

We’ll write a simple function and its test code.

Create a utils folder and add the following file.

export function sum(a: number, b: number) {

return a + b;

}

Create the test code in the same folder.

import { sum } from './sum';

test('adds 1 + 2 to equal 3', () => {

expect(sum(1, 2)).toBe(3)

})

Checking Jest works

Run the following command to execute the test.

npm test

Once you’ve confirmed it works, you can delete the two files above.

Introducing React Testing Library

Now we finally get to the main topic: React Testing Library.

First, install the required packages.

npm install --save-dev @testing-library/react @testing-library/dom @testing-library/jest-dom

Configuration so Jest can handle JSX

We’ll specify how to transform the files under test using a specific transformer tool. Simply put, this defines “how Jest should process files.”

import type {Config} from 'jest';

const config: Config = {

clearMocks: true,

coverageProvider: "v8",

preset: "ts-jest",

testEnvironment: "jest-environment-jsdom",

+ transform: {

+ '^.+\\.(ts|tsx)$': ['ts-jest', { tsconfig: { jsx: 'react-jsx'}}],

+ },

setupFilesAfterEnv: ['./jest.setup.ts'],

};

export default config;

-

Process .ts and .tsx files

Jest converts TypeScript files into executable JavaScript.

This allows you to directly test test code and components written in TypeScript. -

Properly interpret JSX syntax

When testing React components, JSX syntax (e.g. <div>Hello</div>) is correctly interpreted and transformed into executable JavaScript. -

Perform TypeScript type checking and transpilation at the same time

ts-jest can also perform TypeScript type checking.

If there are type errors during test execution, they will be reported as errors.

Creating the component to test

Create a components folder and add an App component.

export function App() {

return <div>Hello Next.js</div>;

}

Test code for the component

Now we’ll use the packages we installed earlier to write test code for the component.

Before writing the test, let’s first render the component and check that it renders correctly.

import { render, screen } from '@testing-library/react';

import { App } from './app'

describe('App', () => {

it('renders App component', () => {

render(<App />)

screen.debug()

})

})

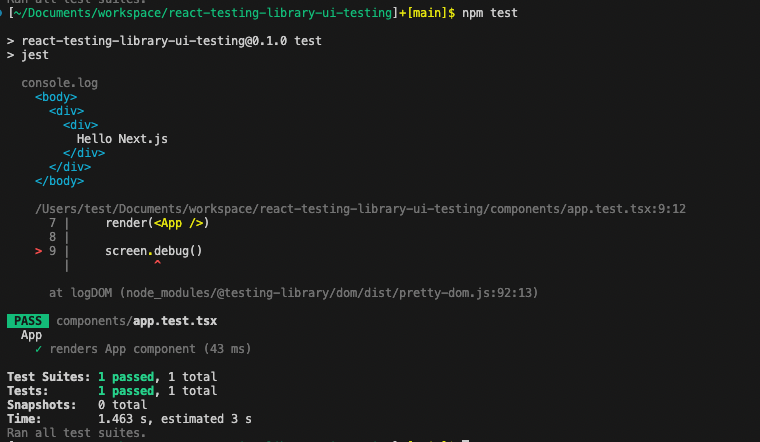

After rendering the component, we use the screen.debug() method.

This is a handy method when writing tests, as it lets you inspect what was rendered.

If you’re testing a component you implemented yourself, you probably already know what will be rendered, so you may not need it.

However, you might use it when adding tests to components written by someone else.

When you run this test, you’ll see output like the following:

You can confirm that Hello Next.js wrapped in a div tag is being rendered.

Now that we’ve confirmed that the text is rendered, let’s write an actual test.

import { render, screen } from '@testing-library/react'

import { App } from './app'

+ import '@testing-library/jest-dom'

describe('App', () => {

it('renders App component', () => {

render(<App />)

- screen.debug()

+ expect(screen.getByText('Hello Next.js')).toBeInTheDocument()

})

})

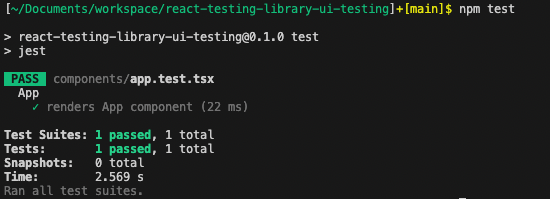

This is a very simple test that checks that the text Hello Next.js is rendered.

Since we’re using toBeInTheDocument(), we also import @testing-library/jest-dom.

Run the test again and you’ll see that it passes.

Tests involving events

Next, we’ll create a component where the user inputs text and test whether the entered content is rendered correctly.

Create a new Search component.

import { useState } from "react";

export function Search() {

const [search, setSearch] = useState('');

function handleChange(event: React.ChangeEvent<HTMLInputElement>) {

setSearch(event.target.value);

}

return (

<div>

<Input value={search} onChange={handleChange}>

Search:

</Input>

<p>Searches for {search ? search : '...'}</p>

</div>

);

}

function Input({

value,

onChange,

children

}: {

value: string,

onChange: (event: React.ChangeEvent<HTMLInputElement>) => void,

children: React.ReactNode

}) {

return (

<div>

<label htmlFor="search">{children}</label>

<input

id="search"

type="text"

value={value}

onChange={onChange}

/>

</div>

)

}

We use useState to manage the entered value and display it.

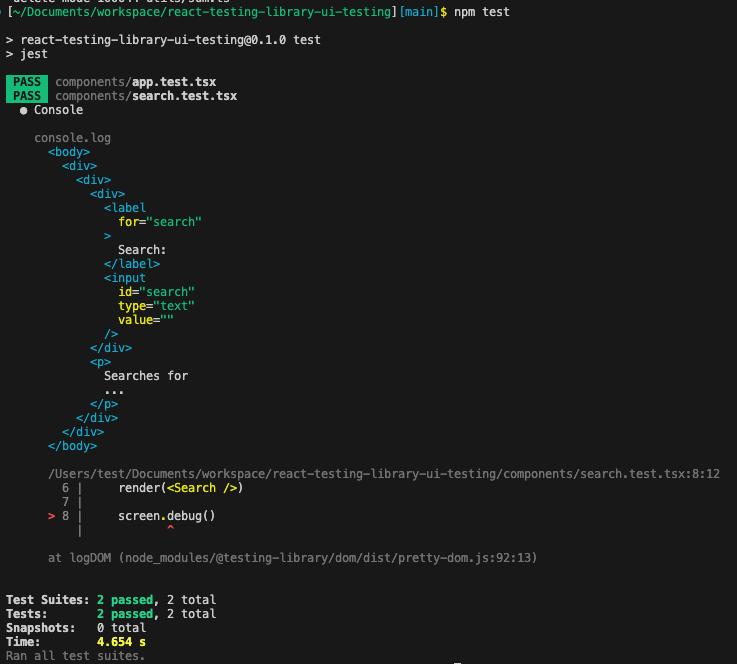

We’ll write the test code, but first let’s render it once and inspect the DOM structure.

import { render, screen } from '@testing-library/react'

import { Search } from './search'

import '@testing-library/jest-dom'

describe('Search', () => {

it('renders Search component', () => {

render(<Search />)

screen.debug()

})

})

You can see that the input tag for entering text and the p tag that displays the entered content are rendered.

Since nothing has been entered yet, ... is displayed after Searches for.

As you may have already noticed, things like useState and the handleChange function that appear in the actual code do not appear in the rendered result.

Also, although we split the implementation into two components, at render time they appear as a single DOM structure.

React Testing Library is used to interact with React components as a human would.

Humans see the HTML rendered from React components, so they see this HTML structure as the output, not the two separate React components.

Now that we’ve confirmed the rendered content of the component, let’s actually input some text.

We’ll use React Testing Library’s fireEvent to simulate text input and button clicks.

- import { render, screen } from '@testing-library/react'

+ import { render, screen, fireEvent, waitFor } from '@testing-library/react'

import { Search } from './search'

import '@testing-library/jest-dom'

describe('Search', () => {

it('renders Search component', () => {

render(<Search />)

+ fireEvent.change(screen.getByRole('textbox'), {

+ target: { value: 'Next.js' },

+ })

+ waitFor(() =>

screen.debug()

+ )

})

})

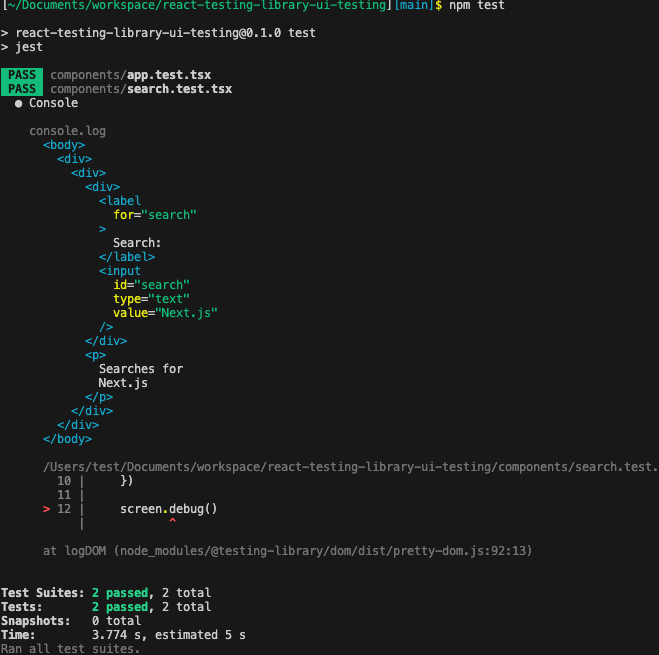

The fireEvent function takes an element (here, the input field with the textbox role) and an event (here, an event with the value "Next.js").

After input, we render again and check that the entered content is reflected.

Here is the test result:

You can see that the text Next.js is reflected in the value of the input tag and displayed after Search for.

We added waitFor before displaying the rendered result.

waitFor is necessary because after using fireEvent.change to change the value of the search box, the re-render may happen asynchronously.

Specifically, an element like screen.getByText(/Searches for JavaScript/) may not be rendered immediately after fireEvent, but may be updated slightly later.

Now that we’ve visually confirmed that the component renders correctly, let’s make it more like a real test:

we’ll test that when the text Next.js is entered, Search for Next.js is displayed.

describe('Search', () => {

it('renders Search component', () => {

render(<Search />)

fireEvent.change(screen.getByRole('textbox'), {

target: { value: 'Next.js' },

})

waitFor(() =>

- screen.debug()

+ expect(

+ screen.getByText(/Searches for JavaScript/)

+ ).toBeInTheDocument()

+ )

})

})

In this way, React Testing Library allows you to test the behavior of components when users interact with them.

Creating a setup file

So far, whenever we used toBeInTheDocument() in our test code, we imported @testing-library/jest-dom.

When writing component tests, you’ll very often use various methods from @testing-library/jest-dom.

- toBeInTheDocument()

Checks whether an element exists in the DOM.

expect(screen.getByText('Hello')).toBeInTheDocument()

- toHaveTextContent()

Checks whether an element contains specific text.

expect(screen.getByRole('heading')).toHaveTextContent('Welcome');

- toBeVisible()

Checks whether an element is visible to the user (i.e., not hidden by CSS such as display: none or visibility: hidden).

expect(screen.getByText('Click me')).toBeVisible();

- toHaveAttribute()

Checks whether an element has a specific attribute or whether an attribute has a specific value.

expect(screen.getByRole('button')).toHaveAttribute('disabled');

expect(screen.getByRole('button')).toHaveAttribute('type', 'submit');

- toHaveClass()

Checks whether an element has a specific class.

expect(screen.getByTestId('my-element')).toHaveClass('active');

- toHaveStyle()

Checks whether a specific style is applied to an element.

expect(screen.getByText('Hello')).toHaveStyle('color: red');

- toContainElement()

Checks whether a given parent element contains the specified element.

expect(container).toContainElement(screen.getByText('Child Element'));

- toBeEmptyDOMElement()

Checks whether an element is empty (has no child elements or text).

expect(screen.getByTestId('empty-div')).toBeEmptyDOMElement();

- toHaveFocus()

Checks whether an element currently has focus.

expect(screen.getByRole('textbox')).toHaveFocus();

- toBeDisabled() / toBeEnabled()

Checks whether an element is disabled (has the disabled attribute).

expect(screen.getByRole('button')).toBeDisabled();

- toHaveValue()

Checks whether elements such as input or textarea have a specific value.

expect(screen.getByRole('textbox')).toHaveValue('Next.js');

Because of this, when writing test code you’ll very often need to import @testing-library/jest-dom.

So I’ll show you how to create a Jest setup file that always imports @testing-library/jest-dom before tests run.

Create a jest.setup.ts file in the project root and add the import.

import '@testing-library/jest-dom'

After creating the setup file, add one line to jest.config.ts.

import type {Config} from 'jest';

const config: Config = {

clearMocks: true,

coverageProvider: "v8",

preset: "ts-jest",

testEnvironment: "jest-environment-jsdom",

transform: {

'^.+\\.(ts|tsx)$': ['ts-jest', { tsconfig: { jsx: 'react-jsx'}}],

},

+ setupFilesAfterEnv: ['./jest.setup.ts'],

};

export default config;

That completes the configuration.

Finally, as a sanity check, remove the line that imports @testing-library/jest-dom from the test code and run the tests.

import { render, screen } from '@testing-library/react'

import { App } from './app'

- import '@testing-library/jest-dom'

describe('App', () => {

it('renders App component', () => {

render(<App />)

expect(screen.getByText('Hello Next.js')).toBeInTheDocument();

})

})

Conclusion

In this article, we introduced React Testing Library and implemented UI component tests using actual components.

We also implemented tests for behavior that responds to user actions (events), allowing us to verify that components provide their functionality correctly.

Shared components are often used across many screens, and even small changes can have a large impact.

I hope implementing UI component tests will provide a foundation for stable maintenance and operation.

Questions about this article 📝

If you have any questions or feedback about the content, please feel free to contact us.Go to inquiry form

Related Articles

Test Automation with Jest and TypeScript: A Complete Guide from Basic Setup to Writing Type-Safe Tests

2023/09/13Implement E2E tests with Playwright to achieve user-centric testing including inter-system integration

2023/10/02Test Strategy in the Next.js App Router Era: Development Confidence Backed by Jest, RTL, and Playwright

2025/04/22Complete Guide to Web Accessibility: From Automated Testing with Lighthouse / axe and Defining WCAG Criteria to Keyboard Operation and Screen Reader Support

2023/11/21Chat App (with Image/PDF Sending and Video Call Features)

2024/07/15Practical Component Design Guide with React × Tailwind CSS × Emotion: The Optimal Approach to Design Systems, State Management, and Reusability

2024/11/22How to Easily Build a Web API with Express and MongoDB [TypeScript Compatible]

2024/12/09Express (+ TypeScript) Beginner’s Guide: How to Quickly Build Web Applications

2024/12/07